Egypt, the land of museums!

In this blog Abeer Eladany, Curatorial Assistant at University of Aberdeen Museums and Special Collections and an MGS Board Member, talks about a recent trip to visit museums in Egypt, the changes taking place in them, and connections to Scotland.

It’s been over 10 years since I visited any museum in Egypt. Two conferences in November, one in Cairo, organised by the American Research Center in Egypt – ARCE and few days later another in Luxor organised by International Committee for Egyptology in the International Council of Museums (CIPEG), as well as a long overdue visit to my family, were all good reasons to go to Egypt. It was also hard to miss an opportunity to visit all the new museums that have opened, including the National Museum of Egyptian civilisation (NMEC), the newly renovated Islamic Art Museum, and the Coptic Museum.

A well organised pre-conference excursion by the CIPEG committee included museum visits from Cairo to Luxor, as well as daily trips around Luxor to visit temples, open air museums and archaeological sites, and a special trip to the city of Esna to explore its new Cultural Heritage Assets (RECHA) project. The imminent opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) was also a huge attraction to visit.

I thought a visit to the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir, where I used to work between 1991-2003, would be a good place to start. When I queued to get a ticket I noticed it has increased for Egyptians and for tourists. Museums in Egypt are not free and the income from the tickets help keep these museums open and support the free activities they offer to school children.

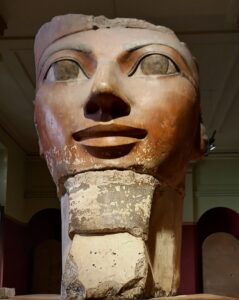

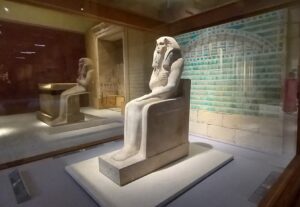

There is a dramatic change at the entrance of the museum due to the relocation of the book shop that used to be the first thing you see after the large wooden museum doors. The display still follows the chronological history of Ancient Egypt starting from the prehistorical period and highlights all the master pieces throughout the dynasties. There was a noticeable improvement regarding the lighting, showcases and labels which are written in both Arabic and English. I was very pleased to see some wonderful ideas implemented, for example, the new display of the famous Meidum Geese, a wall painting from the early 4th Dynasty tomb of Nefermaat and Itet. The fragment is displayed now within the context of a replica tomb wall with other fragments that belong to the same wall scene.

These display improvements are part of “Transforming the Egyptian Museum Project” which was launched in 2019. It is a collaboration between Egyptian curators and conservators together with their European counterparts from The Museo Egizio (Turin), The British Museum (London), The Louvre Museum (Paris), The National Museum of Antiquities (Leiden), and The Egyptian Museum (Berlin).

After a while I found myself thinking about parallels to the Egyptian collection in Aberdeen, and in Scotland in general. I was looking for links to Aberdeen in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and I was not disappointed, as many replicas were taken from the originals in Cairo and shipped to Aberdeen. I was excited to see the original Canopus Decree and the statue of Amunirdis on display and compared them from memory to the Aberdeen replica collection. Examples of predynastic flint knives and arrowheads made me think of those that are collected during fieldwalking days with the Mesolithic Deeside group and of Scottish flint tools from the collection in Aberdeen.

Relief fragments from the funerary temple of Sahure on display on the ground floor reminded me of the relief fragments from the same temple housed in Aberdeen. Thinking of reuniting fragments virtually or through replicas, I could see examples of fragments united through replicas already on display in the museum. See this example of a statue of Amenhotep III where the head is in Cairo and the body is part of the University of Durham Collection.

Some of the objects on display at these side rooms were like objects housed in Aberdeen. Due to the way the objects in Cairo are collected, the find location is almost identified for every artefact and I found myself trying to gather this information to help identify possible sites for the Aberdeen artefacts. However, not all the objects on display in the museum have labels.

As a proper museum geek, I was paying attention to different aspects of the display, the condition of the objects, and when I saw environmental monitors, I looked at the readings. My biggest surprise was at the end of my visit. A large section of the back and side areas that were previously used for offices, has now transformed into a substantial gift shop. This also includes a café and some food outlets, including fish and chips!

I couldn’t help but think about repatriation/ rematriation and decolonialisation while visiting the museum and what can be done. Due to its colonial past, the museum always had European directors. In 1941, its first Egyptian director, Mahmoud Ali Hamza, was appointed. Hamza was an Egyptian Egyptologist who studied Egyptology at the higher Teachers’ Training College in Cairo, the Institute of Archaeology, Liverpool, and at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. I wonder how much he was able to influence the display and interpretation that lasted for decades before he was appointed. His time as a museum director took place while Egypt was still under the British colonial powers.

I always think about different ways of collaboration and knowledge exchange with our colleagues working in the museums in Egypt. I’m really looking forward to going back again next year, spending more time in the museum, and discussing different challenges in the sector with my Egyptian colleagues.